Culture is more than just food, clothing, or way of life. It is the collective equivalent of an ego, and as nations change, their cultural narrative changes with it. In this episode, I explore how technological changes in India and Japan affected their culture narrative, and how the shifting borders affected the culture narrative of Latvia and Germany.

Hello everyone and welcome to the fifth episode of Baggage Allowance. In the last three episodes, I explored the topics of religion, history, and ideology. A recurring realization I had was that each of these subjects had a lot more to with peoples’ identities than I previously acknowledged. I want to now address the subject of identity, namely cultural identity, head on. I will begin by fulfilling a promise I made in the third episode by describing in more detail the cultural transition of Japan.

As a refresher, Japan underwent a period of rapid modernization during the Meiji restoration in the second half of the 19th century. During this time period, the military took full control of the country and organized massive nationwide industrialization and modernization projects. On the tailcoat of these reforms came wholesale cultural transition. Women began wearing European dresses and shoes. Men began wearing suits and ties. Children started going to school in western style uniforms. People began eating with a knife and fork when, in the past, having a knife at the table would be seen as savage.

A good illustration of this clash between new and old can be found in Kyoto at the Nanzenji temple. The temple complex is huge and dates back 800 years. The buildings within the complex were made entirely of wood and stone. Not even metal nails were used, the wood was carved such that the structures would hold together even without nails. The exception to this though is the Kyoto Aqueduct which cuts through the temple grounds. It is made of brick and was built during the Meiji restoration. Functionality aside, this Roman style aqueduct felt very out of place in comparison to the rest of the temple structures. However, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. While the source of much controversy during its construction, the aqueduct has now become a favorite spot for Japanese people to take photographs at. So, in a huge temple complex full of beautiful Japanese gardens, temples, gates, and shrines, one of the most popular spots to take photographs at is a Roman style aqueduct. Now to be fair, construction like this is really rare in Japan even today, so it may just be a case of novelty attracting curiosity. But in a way, I also think it sort of alludes to the Japanese culture dilemma.

The West has, for better or worse, come to represent strength, beauty, and wealth. One Japanese businessman I spoke to even called it the Japanese inferiority complex. I thought that was harsh, but I can see where he is coming from. For example, billboard commercials for makeup and fashion always featured European models. These weren’t out-of-touch foreign brands either. Japanese companies making products for Japanese women were using European models in their commercials. And despite low English fluency, many advertisements in Japan were using English words and phrases. As a native English speaker, I felt the slogans and words made no sense in the context of the ad, but that didn’t matter. These ads were targeting Japanese people, not English speaking tourists.

“Western” in Japan has become almost the equivalent of “hipster” in America. Bakeries that sell Western style bread in Japan are like boutiques. Even by Japanese standards, the presentation and service was extraordinary, and naturally the prices were higher too. In fact, anything that could market itself as “Western” had a premium tied to it. And on the other extreme, traditional Japanese things were tucked away and almost unseen. Before returning home, I thought it would be nice to buy some traditional Japanese cloths. Many souvenir shops were selling them, but I figured they were overpriced, so I went to mall to buy something there. To my shock and amazement, none of the stores I visited carried any traditional clothing for men. One of the sales clerks even tried to help me by calling all the other stores in the mall, and not a single one had traditional men’s clothing. I asked him where he got his traditional cloths from (assuming he had some at home). “I never bought any,” he replied, “I have some at my parents place, they got it for me.”

I contemplated the possibility that maybe no one wanted to go through the hassle of explaining and selling traditional cloths to a foreigner and just wanted to direct me to souvenir shops. I also contemplated the possibility that malls just weren’t the place people go to if they wanted to buy traditional clothing, but the salesclerk helping me seemed just as shocked as I was that no store in this giant mall carried anything. Maybe my luck would have been different had I come before the summer bon festival or some other function, or maybe I was just flat out unlucky and picked the one mall in Japan that had no traditional clothes. I ultimately did not buy anything during my trip.

Now Japan’s cultural transition began over a hundred years ago, but what about countries like India? They industrialized much more recently, so their cultural transition is still taking place. Here, I observed a divide between traditionalists and modernists. Traditional men were still wearing traditional cloths on a daily basis, though some also wore khakis with a button down shirt if their jobs require them to. By contrast, modern men can be seen with ear-rings, lots of gel in their hair, and wearing (supposedly fake) leather jackets. Traditional women were still wearing traditional cloths, while modern woman could be seen wearing form fitting shirts and pencil skirts. Around the time of my arrival, short skirts and hot pants were causing some local controversy. One of the men I spoke with was outraged at the Americanization of India. He complained that the youth were forgetting traditional values like modesty. When I commented that perhaps they just wanted to wear what was comfortable, he countered by asking whether it be okay for him to sit on the bus in his underwear because it was comfortable. I backed off, but that same day I saw a cartoon in the local newspaper that perfectly illustrated my thoughts. In the cartoon, two woman were complaining to each other about how a younger girl who just walked past them was being immodest. The traditional woman were wearing saris which exposes some skin around the stomach. Meanwhile the younger girl was wearing a t-shirt and some jeans, with the t-shirt exposes just a little of her midriff. The hypocrisy was clear.

Beyond clothing and modesty, other aspects of – quote – “American culture” that was apparently eroding Indian society included greed, consumerism, unhealthy eating habits, drugs, and the youth sleeping around. While these might sound familiar, the perception of “American culture” was still very distorted. Or more precisely, it became whatever the speaker wanted it to become. If they wanted India to industrialize and modernize, the United States is everything good that India wasn’t: industrious, organized, strong, and good with money. One engineer commented that it would have been better if the United States occupied India like they did Europe or Japan after WW2. His was obviously a fringe minority view, but I think it illustrates his idealism of the foreign culture. On the other hand, if you want India to remain traditional, the United States is everything India has become that you dislike: violent, greedy, narcissistic, unhealthy, rude, and immoral.

Squabbling aside though, India, much like Japan, has a strange big brother attitude to the United States and the West. Getting a job with an American or European company or a degree from an American or British university is very prestigious. It does not matter what university or company it is. And while advertisements in India feature Indian models, they all tend to have pale, almost white skin.

I basically have come around to seeing this kind of behavior the same way I see employees in an office trying to emulate the boss. If the boss dresses formally everyday, the employees dress formally everyday. If the boss comes in early and leaves early, the employees come in early and leave early (but only after the boss himself leaves). If the boss recommends a book, the employees will read it so that they can speak the boss’s language. Employees may hate them, but they still mimic them.

Now emulating those doing better than you is not necessarily a bad thing. It helps to be associated with the right group of people. However, if you are just emulating others, who are you? This identity crisis is playing out at a societal level in countries like India and Japan. In this way, culture can be seen as the collective equivalent of an ego, and its only function is to separate I from they, and different cultures have found different ways of doing that.

The Japanese are direct, it is based off of race. It does not matter how fluently you speak Japanese, or how long you lived in Japan, or even if you were born in Japan, if you don’t have Japanese blood, you can never understand Japanese culture or be Japanese. Many Europeans want to say the same thing, but doing so will get them slammed for racism, so they invented creative ways around it. The most common one is language, best illustrated by an Egyptian I met, who had been living in Finland for over 10 years. He speaks Finnish fluently, and I asked him whether Finns thought he spoke with an accent. He responded that it depends on whether they thought he grew up there or not. In other words, if he introduced himself as a Finn who grew up in Finland his whole life, they would think he had no accent. On the other hand, if he introduced himself as an Egyptian living in Finland for 10 years, they would comment he had a – quote – “almost perfect accent”. And that’s the rub. Most people would assume he is an immigrant based on his appearance and so they could hear an “accent”. And you could never truly be a Finn unless you speak the language perfectly. It is race with extra steps and some exceptions.

Okay, but what about larger more ethnically and linguistically diverse countries like say India or Indonesia. Indonesia has 633 recognized ethnic groups. India has 22 languages recorded in its constitution. Should each of these ethnic and linguistic groups be treated as a separate culture each, thus implying the nations are multicultural. Or does each country have only one culture, which just so happened to include many ethnic and linguistic groups?

Indonesia’s motto is “Unity in Diversity” so they made their choice. India seems more divided on what path they should pursue. Hindu nationalists want to make India a Hindu nation, thus carving a clear culture boundary for what it means to be Indian. However, they face opposition from those who wish to see the nation of India as a secular nation. There are also political parties in the south of India that vocalize linguistic cultural differences, but they seem to have mixed popularity. On the whole, it seems the multilingual nature of India is not an obstacle for having a unified culture. On my trips, I came across a few families where the parents spoke different languages. That is not unusual, I have seen it all over the world. What was unusual though was that they did not see their relationship as an intercultural marriage. As far as they were considered, they enjoyed the same food and prayed to the same God. They grew up with the same youth pop culture, through translations of the same books and movies. The difference in language only mattered when speaking with grandparents.

Now, if India chooses the path of multiculturalism, does this mean Indians, as a whole, do not share a common culture? Well, let’s look at other multicultural nations to answer that question. The United States, as whole, shares a single culture. However, San Francisco and New York have their own unique cultures as well. Germany, as a whole, shares a single culture, but Bavaria and Berlin each have their unique cultures as well. In the same way, India as whole would share a culture, but Bengal and Kerala would have their unique cultures (and it this particular case languages) within it.

Cultures can be seen like a hierarchy. There is a broadly encompassing culture at a national or supranational level, then regional or state cultures, and then even smaller local cultures. But that presents an interesting thought experiment. Suppose San Francisco decided they had enough with the rest of the country and successfully seceded from California and the United States. With San Francisco as it own nation, there will now be a Wikipedia page created for the “Republic of San Francisco” and it will have its own culture section. Now in the past, when people referred to San Francisco culture, they would be referring to it as a local culture, within Californian or American culture, but now it has to suddenly be seen as its own separate culture. Yet, apart from becoming its own nation, nothing really changed. So is San Francisco culture still a subculture of the United States, even though it is no longer part of the nation?

This may seem like a contrived question, but there are several instances of countries breaking up or unifying throughout history, and the cultural narratives change to match. For example, how would you describe the culture of Latvia? That is an explosive question. Latvia for a good duration of its history was part of Russia, and now about a third of its population is Russian. However, sense Latvians did not appreciate being annexed by Russia and the Soviet Union, suggesting that they share cultural similarities with Russia today would usually be met with push-back. There are exceptions though.

When I was in Latvia, I stayed with a man who spoke both Russian and Latvian. This was common, most middle age Latvians seem to speak both, but it made it difficult for me to tell whether he self-identifies as ethnic Russian or ethnic Latvian. I didn’t dare ask, but I was dying to know, because he commented that he felt Latvia shared more in common with Russia than the European Union. If he was ethnic Russian, this would make complete sense in my mind. However, if he was not ethnic Russian, this would take me by surprise, because Latvians (and other East Europeans) want to do everything they can to distance themselves culturally from Russia.

When speaking with people, especially young people, from Eastern Europe, if I refer to their nation as part of “Central Europe” instead of “Eastern Europe,” they become much more talkative and friendly. 10 years ago, East Europeans were competing with each other to call their nation the “center” or “heart” of Europe. They so wanted to distance themselves from Russia that they even wanted to change geographic nomenclature to add distance between themselves and Russia.

Now these are all examples of a culture wanting to break association with another, but the reverse can also take place. When nations merge, the national propaganda rewrites the narrative to make it seem that the cultures are in fact subcultures of the same single culture. Germany is an excellent example. For most of its history, Germany was not a single country. It consisted of many smaller kingdoms that constantly fought each other. Yet the nationalist movements in the 19th century wrote the narrative that this was all a common history that simply contained many players. Yet if history was just a little different, I could easily imagine two nations in what is currently Germany each claiming to have its own unique culture. The two nations would be Catholic Southern Germany and Protestant Northern Germany. I am not suggesting there are religious divisions in Germany today. Much like the rest of the West, Germany has mostly secularized. However, when wandering around towns in the south of Germany, I would find Catholic paintings lining the side of paths and roads leading up to churches. I have seen this at Catholic churches all over the world, but in Southern Germany it was so prevalent that I think the only place I saw more was in Italy itself. I could easily imagine a time, when religious differences were much more important, that these regions had other distinctions that could have possibly even triggered them to form their own nation and encode their own culture.

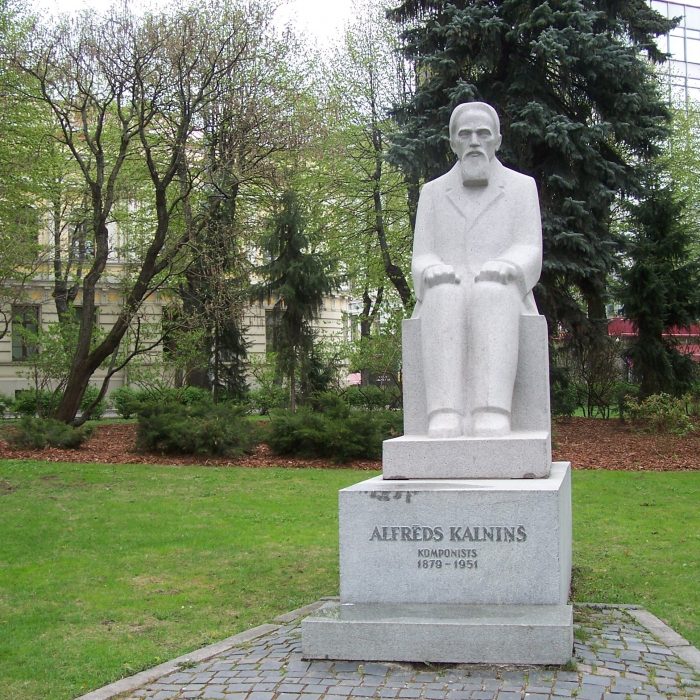

And that’s another interesting thing I realized: nearly all modern cultures were encoded relatively recently. While all cultures like to claim existence from the beginning of time, the fact is that most nationalistic movements, and the cultures they immortalized, came to be in the last 200 to 300 years. I have seen statues and buildings over two thousand years old in Italy, but the current narrative of a unified Italian culture is only about 200 years old, and Italy only became a single unified country in 1871. Go to any national museum in Europe, and you will find that a great deal of their exhibitions date from the 18th century or later. Artifacts that are more than 400 years old were gathered in research expeditions in the 19th century, when the field of archaeology began to take off. The artists, composers, and writers nations take pride in today are coincidentally the same ones that nationalists promoted 100-200 years ago.

Now I don’t mean to bring all this up to suggest that culture is just something humans made up. There are differences in what people of different cultures consider beautiful, and what they value, believe, and live by. Part of the pleasure of traveling is to witness and observe these differences, and I will spend the next few episodes exploring these. However, just like ideology, religion, and history, culture has become a part of people’s identity, and when it comes to identity, people have a tendency to bend definitions and boundaries to include the people they want to include in their tribe, and exclude the people they want out of their tribe. This becomes problematic in countries going through a lot of change and transition, because differences between people within their own culture become wider while the distance with foreign cultures begin to shrink. As the seek ways to distinguish themselves, many will turn to race, language, and religion. This is sometimes accompanied by a rewrite of the cultural narrative itself.

As globalization continues to remove geographic and other barriers between cultures, I think change and transition will only accelerate. It is going to become even more difficult for nations to hold onto their unique culture narratives. Are they going to double down on religious, linguistic, or ethnic differences, or are they going to just let it go? The idea that millions of people in a nation share a unique culture is only 200 to 300 years old. It coincides with nationalism and the industrial revolution. It marked a transition from people having regional and religious identities to having national identities. There is no reason to hold on to this forever.

That’s all for this episode. Now, the last few episodes have been rather intense, so next episode is going to be more chill. I am going to talk about design differences in common everyday stuff like food, houses, bicycle lanes, etc. It’ll be fun, so until next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS